In 1975, when I met Percy Danforth, the father of modern-day rhythm bones, I’d been playing folk music professionally with my twin brother, Laz, as the duo Gemini, for about two years.

Like most good folkies of the day, we played guitars and sang. But around that time Laz also picked up violin, after having abandoned it in high school some years before, and we also both got interested in Irish music. Laz started learning the pennywhistle and I made a crude bodhran and we began playing jigs and reels in our shows.

We were living in Ann Arbor and one night Laz saw Percy play rhythm bones in Donald Hall’s play Bread and Roses. (Donald Hall was a renowned poet, playwright, essayist and critic, and from 2006 to 2007 was the fourteenth US Poet Laureate.) Laz told me about Percy very excitedly. “You won’t believe what he can do with just four little pieces of wood!” I was intrigued and called Percy and asked if he would teach me how to play. He generously said he would, but said he’d been getting a lot of requests lately. Would I organize a rhythm bones class for him at the Ark, Ann Arbor’s famed coffeehouse?

I called Dave Siglin who, along with his wife Linda, were the co-founders of the Ark, and a couple of weeks later about twenty of us gathered in the Ark’s living room and Percy showed us the tap and roll, the basic rudiments of rhythm bones playing.

I was not a quick study—to put it generously. Now, forty-five years later, when I introduce rhythm bones at our concerts or bones workshops, I show people what I looked and sounded like for the first few days I played rhythm bones.

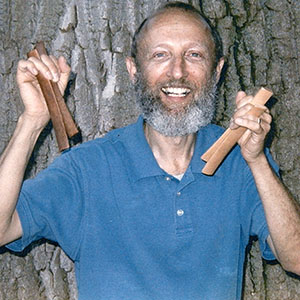

After Percy’s rhythm bones maker, Ray Schairer, passed away, I took over his workshop and make Danforth rhythm bones.

Sandor’s Media